Doing a “first” where the way and how of exploration is not known deeply attracts me. What seems a physical accomplishment is more deeply discovering oneself. Found in this discovery is the great beyond. Physical exploration opens understanding similar to that from prayer or meditation.

When going where no one has gone before, a route is found, but the discovery is more than the route … which later others or yourself can follow again. Those allow doing the journey better. But in going first, what becomes known is the unknown.

Prayer and meditation is for me not a saying of words, but extending myself into the Divine. What is entered is the unknown that knows so much, the ground of all being. In entering what comes back is mercy and love.

Such exploration is entering into the mysterious space of going down paths not known and touching The Wild (life not controlled).

The journey tests oneself, not in conquest but in an inquest to find deepest meaning.

Discovering mystery of the Great Beyond has happened for me with climbing mountains previously unclimbed, also descending rivers previously not human traveled. In ‘discovery’ of the Yeti, as an animal, even more powerfully as an icon, merged physical and spiritual exploration. What came was understanding of existential depth of life. I came up close to humanity as wild and became a neighbor of God.

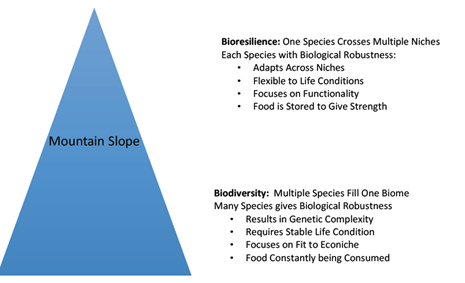

Bioresilience: A New Way to Understand Place of Life with Nature

As a young boy growing up in the Himalaya, I noticed flowers bloom at different times over the span of the 1,000-foot climb from school to our home at the top of the hill. I began to see that an aspect was missing in my biology textbooks. The textbooks said that the tropics was where life was most robust; a diversity of species created that strength—but it was clear to me that life was robust in a different way on the mountains.

Yes, life at the bottom of mountains was robust in wealth of species found there. But, overlooked was robust life at mountaintops where fewer species lived. Life up high had an ability to endure harsh and varying conditions.

Both types of biological robustness (diversity of species and hardiness of one species) are strengths. But they were not the same. Wealth of species gets its strength with genetic diversity. The other strength allows life to exist in a diversity of climates (less oxygen and colder) where only a few species can endure the fluctuating climatic diversity—this is a different biological strength. (Gentians can burst through snow and still bloom; this is an example of this other strength as most flower veins burst and lose their ability to bloom after freezing has begun.)

Temperature is not the only aspect changing in mountains. Turning a ridge, the sun’s energy on a slope can decrease, maybe by half. Change in moisture can be similar, as ridges alter the clouds dropping the rains. Sun, moisture, oxygen, soil, even the stability of the slope flux in mountains, and to these life if it is to endure must strengthen—not just surviving, but thriving.

I found no terminology in the biological literature to explain this. So, I created a new term: bioresilience, a term I introduced in my book Something Hidden Behind the Ranges (San Francisco: Mercury House, 1995).

Rising altitudes have a thinning blanket of air to buffer temperature change. So when the sun goes down (because plants cannot run indoors for shelter), not only must vascular systems empty fluids to prevent rupture from freezing, but in shutting down they must be poised to bounce back to maximize time when the sun’s energy returns, driving metabolism, respiration, and photosynthesis. And, in these shortened periods, for continuity of a species, reproduction must not be disrupted. Accommodating change is essential when the climate fluctuates.

In bioresilience, the focus is on function. Gender differences lose their decoration. Food sources, which may be deprived for half the year, must harbour nutrients in roots and rhizomes, body fat, or underground caches. Bioresilient plants avoid the complex reproduction rituals found in the biodiverse tropics, preparing sometimes for reproduction a year before they procreate (for example, the high-altitude flower-bud primordia).

Without bioresilience, hardiness of life would be limited to a girdle around the planet.

Like the bounce of any ball, this world will not rebound from the now-coming changes unless we engage the flexibility of our whole sphere. One way is with one species adapted to each niche—biodiversity. Another way is to have species that are able to cross multiple niches—bioresilience—fitting many conditions. And so, God bless those species that are everywhere: cockroaches, crows, zebra mussels, and yes, humans too.

Excerpted from Yeti: The Ecology of a Mystery (Oxford University Press, 2017, pp169-173)

1st Descent of Nepal’s Sun Kosi River

Arriving at the banks, apart from the currents, our lives stood in a circular whole. Attention could roam and choose through 360 degree perceptions. But when pushing into the river, the river took hold and we were directed by the force. We cascaded down a vibrating line. A once-circle of options became a defining line. We knew only upstream and had just one future: down, bringing forward life questions about what was before not knowing. If we willed, we could stop here, there, seemingly anywhere. But such were just pauses on the line we tumbled of questions on the until-then-not-solved challenge.

Two hundred miles were lived on this first descent of the Sun Kosi—after four expeditions before us had failed. The first day we lost altitude fast; a rapid every eight minutes. The difficult day was the second, with two rapids we ran just right—for on one rapid the side of the river we bolted down, we avoided a jagged cliff that could have shredded the rubber tubes, and through the other rapid we passed a vacuous hydraulic hole where the river swirled into itself. The third day we rode a memorable half-hour of consistent froth.

Bobbing along beside us for a while, the log then abruptly got sucked into one of those hydraulic holes, a moment later catapulted out. We let it ride on ahead. Our air-filled raft floated with buoyancy a log did not have, and it had energetic oars to swing us around the hydraulic hole’s rim. Sometimes it is best to let life pass.

All river trips are unique voyages, no matter the number of times you take them. The river, every river, is new every day. And in the continual new discovery of this wild, it is a valid urge each of us has to discover the unknown of the way as well as our unknown within.

Today our species pounds forward through human-induced cataracts of a changing climate and a diminishing diversity of species. Our journey brings an ending of the once wild. We have climbed the highest peaks, explored every land, and tamed so many dangers. Few firsts remain—except the unknown journey forward. People ride on a changed planet, not that the planet has changed but rather our understanding of it.

We do not know the larger river of Life we now run. The earlier conceit that initiated the global changes races into currents beyond understanding. What carries us on into the unknown is that we cannot go back. Time, like all rivers, runs in one direction, for even if there is a tide that appears to push the river back, the river always runs on.

On this the first successful expedition down, we were free in so many ways—free from an engagement with the quest, then free from the river when the four of us were standing on its banks talking. We believed the river, like life, was to be a grand adventure, unfolding in grand unpredictable unknowns before us. To assay ourselves we then pushed into the river for testing.

Eddies, rocks, fields, jungles, spirits, and people; a montage of life passing, the river tying all together—the rhythm of rapids punctuating our lives: forward, downwards, made strong by rain and melted snows. Our destiny was to flow with the push of water that came from the sea, coursing us back towards the sea, water having circled to the sky now heading home. We did not choose our direction and only minutely adjusted our speed. Being inside this movement felt as though inside the arteries of the changing planet.

Rapids give news of their arrival first by sound. A growl … then that grows. Rapids first show as a line across the river. The line of river going down has suddenly a line across. Growl then roars; the lower jaw of the river falls open. Into it our raft then went, throwing the weight of the boat back to land prow high, stroking with the oars to pull the raft forward from backwashing into the chomp of the water’s tumbling teeth.

From Nepal’s central hills we drifted into her sparsely settled foothills. Rounding a bend, we entered a sylvan pocket cut off by cliffs all around, a primeval bank where we pulled ashore. Wild jungles stood, seemingly a protected side-valley holding no people. But people had indeed come a stump cut long ago assured us. In one clump of trees were twin banana trees sometime somehow planted with bananas then ripe, fruits for us and fresh rest for our bodies. We lay on the moss, wet and cool and thick.

Back in, in front of our ride, standing up to its knees on a rock in the water and pumping its tail, a white-capped river chat dipped its beak and trilled out ‘SHREE’. Around the next bend, across the river’s span stretched a spider’s web. Its lattice of threads danced with drops scattering light with rainbows. More droplets splashed on to it the instant we approached, quivering on the strands, star prisms sparkling before a blue sky beyond. The current, though, crashed us through, driving us on.

(Excerpted from Yeti: The Ecology of a Mystery, Oxford University Press, pp 124-126)

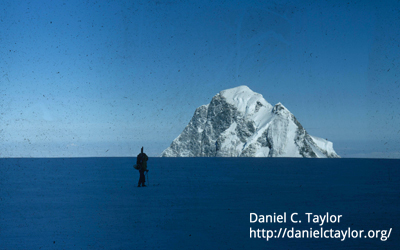

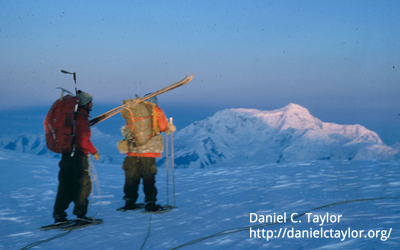

1st Ski Descent of Mount Logan

The summer of 1967 – I was Deputy Director of a team that built a laboratory on the summit plateau of North America’s second highest mountain: Mt Logan in the Yukon Territory of the Canadian arctic. The purpose was to test two drugs thought to help with rapid acclimatization; this was a project of the Arctic Institute of North America. Was it possible to reduce the life-threatening danger of pulmonary edema by taking a pill of Diamox or Lasix before and during a rapid ascent?

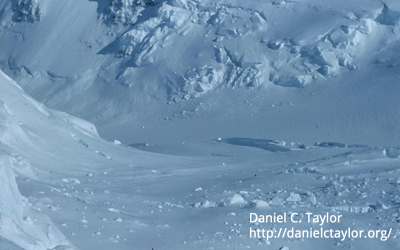

We built the house—and all summer got dumped on by snows. One three-day blizzard gave five feet of snow. The main summit is 19,551 feet, but among the world’s mountains, Logan has the largest circumference of any non-volcanic mountain on Earth; there are eleven peaks on this mountain over 17,000 feet. This mountain has a lot of snow.

So, it was perfect to try and ski down. Deep deep powder. Crevasses the snow so completely covered … I did not know was there until I fell inside. Soft soft powder at high altitudes that tricked my mind to think I was flying … until I flipped. Skis across the top of my pack sometimes bridged the crevasse and kept me from falling too far down.

Truly spectacular vistas across the Logan, Hubbard, and St Elias glaciers!

Driving Overland - Germany to India to Germany - Summer 1968

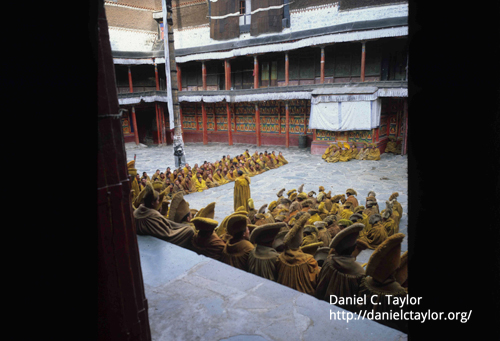

The year 1968 holds significant world events. For me, it stands as a glorious time of adventure when the Middle East was a safe to travel through; its people were exceedingly friendly. During the summer of 1968, with different groups of friends I drove from Germany to India, then after a some months as an advisor with the Dalai Lama's Education Office back to Germany.

Some serious work was done on the educational advising side, but the story here is about adventure. I purchased an even-old-then VW bus in Germany. With it, we outran folks on the Turkey-Iran border who wanted to forcibly stop us (yes, how do you outrun another vehicle in a VW bus--you can do it by hiding but certainly not by speed).

By the 1970s, major modernization would span the three thousand miles from western Turkey to Pakistan, but in 1986, the road we searched out carried the feelings of re-tracing ancient caravans--we felt as though we had driven back centuries in time.

We burned out a first engine in Afghanistan's Baluchistan desert. But, the mechanics of the road are resourceful--other VW buses had been abandoned before ours so earlier-used parts could be salvaged--and we wound our way through the Khyber Pass to into Pakistan, then India.

On the return, heading from India back to Germany, we made an unwise decision in front of the Royal Palace in Kabul--and this time had to outrun Afghan police, but we knew what to do that with a VW bus this time.

Then in northern Afghanistan we nearly burned out the replacement engine (a VW bus draws in its air from the back ... and if a dusty road causes engine trouble).

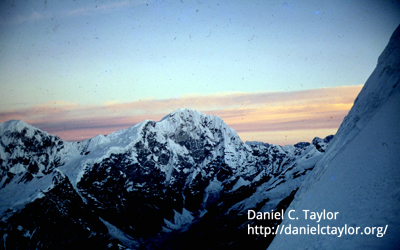

Fluted Peak (Gyangchhempo) – Langtang Valley Nepal – 21,000 feet

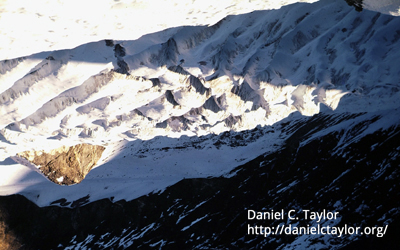

Gyangchhempo is a stunning mountain from every angle. It is the closest ice-capped summit to Kathmandu. During the years I lived in Kathmandu I woke up to a view of this mountain—it had by then been attempted six times unsuccessfully, including by the renowned Bill Tilman.

But one morning I woke up and told myself, I’m going to tackle it. I had to make three tries—the obvious route (right side from Kathmandu) turned out to have significant icefall danger. On the third trip (left side ridge from Kathmandu) we reached our goal. Each attempt was wonderful fun.

The Mountain

1st Attempt

2nd Attempt

3rd Attempt